Holy Transformations: The Topography of Religious Success

Life in Ancient

Ephesus

Classical

Temples

Church

Distributions

The Early

Shrines

(Foss 1979)

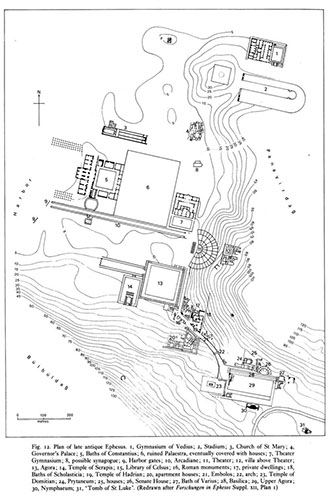

Placed on a plateau between the hills of the Panayirdag and the Bülbüldag, it was the original centre of the urban religious activities, organized around a temple of unknown dedication and protected by a temenos. The square was dedicated exclusively to buildings with a public function, so that no shop nor any other private building faced on this open space.

The importance of the Upper Agora was also stressed by the construction on its western side of the first neokoros (or Domitian’s) temple in the late 1st century AD. A later phase of building activity was started with Hadrian after a small hiatus. In this period, two monumental temples (the Olympieion and the Serapeion) are built at the east of the Panayirdag hill. The Temple of Serapis was located in connection with the Tetragonos Agora and the Olympieion was encircled by a porticus. Yet, the disposition of religious buildings in this area of the city never reached the density of the Upper Agora.

Map by L. Pinchetti, information from J. Vroom.

The classical temples are all located into the Hellenistic urban walls or in the new lands occupied from the Augustan age at the West of Mount Panayır Dağ.

The only exception is the Temple of Artemis, situated at the feet of the Ayaşoluk. Looking at the concentrations of the pagan shrines, we notice that temples are not located evenly in the city. Indeed, the Upper – or State – Agora result to be not only the original core of the socio-political life of the city, but also the focal point around which revolved the religious life of the city.

Map by L. Pinchetti, information from J. Vroom.

Contrarily to the temples, churches are more regularly distributed throughout the entire city and, which can be seen clearly on the map. The only higher density area is located around the so-called Byzantine palace, showing discontinuity with the previous focal centre of the Upper Agora. This regular pattern of churches is likely to have taken form unevenly over a long period of time. In fact, we can assume that the Christian community urged to have new buildings firstly in locations with a special religious meaning. Amongst the fifteen churches identified by Renate Pillinger (1996, map), shrines like the Seven Sleepers, the Grotto of Saint Paul, the tomb of Saint Luke or the Basilica of St. John were possibly built in an earlier phase .

Map by L. Pinchetti, information from J. Vroom.

The four shrines mentioned before (in the section on Church Distributions) are remarkable for their direct relation with the cult of saints, which is likely to have attracted early cultic activities and functioned as pilgrimage centre. All of them follow the rule of the ‘centrifugal effect’ even though they lie in locations with a significant topographical importance.

The tombs of Luke and Saint John for example are located along the two main roads, thus in very visible locations. The only Ephesian church positioned in the centre reuses the structures of the temple of Serapis, and is likely to have been built in a second phase after the 4th century AD, when the pagan shrines were starting being demolished.

In the early Christian period, it seems churches were located on the outskirts of Roman towns, where it was easier to find free plots for its shrines. Topographically speaking, this would imply a fundamental break between the disposition of pagan shrines and early Christian churches.

In our research, we wanted to test if this discontinuity was visible in ancient Ephesus. By analysing the concentrations of the religious buildings, we expected the temples to be disposed mainly around the centre of the city and the ancient churches to have peripheral positions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a radical difference occurs between the pagan and the Christian topography. The well-balanced network of churches, even though pulled together in a long time, opposes the previous nucleation of pagan shrines around the political centres of the town. The layout of Ephesus was adapted to a completely new religious topographic system. The new religion, focused more on reaching the individuals rather than the society, shaped the urban landscape to fit its different cultic necessities.