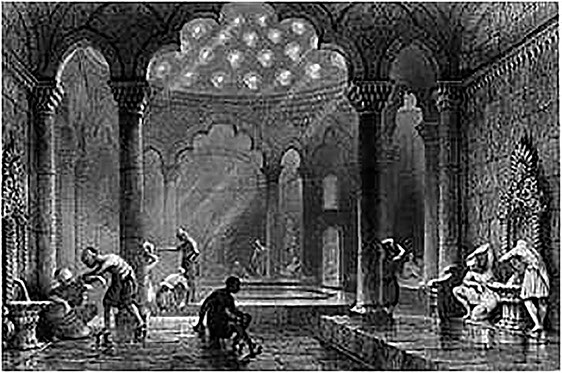

Islamic Baths

This image shows the Hammam Cemberlitas in Istanbul, built in the 16th century. The hammam was designed by architect Sinan, by orders from the mother of Sultan Murat iii of the Ottoman Empire. It is still in use today

In early Islamic contexts, baths become extremely popular, reaching a peak in the 10th century. Writing in the 10th-11th centuries, historian Hilāl al-Sābi estimates that Baghdad at its height held 60.000 hammams! Although this estimate is most likely exaggerated, it does indicate the popularity of the hammam in the Ottoman world.

Following the appraisal of bathing by the prophet Muhammad himself for its positive effects on fertility - the word hammam derives from the Arabic phrase for ‘spreader of warmth’ – bathing became more and more connected to religion

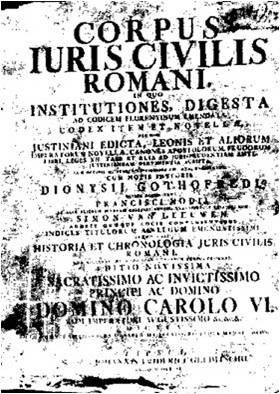

The Justinian Codex describes a law from the 6th century stating that the Government is obligated to take care of grain supplies, the construction and maintenance of waterworks and ports and the financing of baths.

As can be seen in this legislation, bathing was extremely important in daily life. However, during the 7th century it became more of a luxury practise.

One example from literary sources concerns a young man of high social standing who visited the baths once a week, in order to maintain his cleanliness and beauty.

Image showing the text of the Justinian Codex and a picture of Justinian himself.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Justinian_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corpus_Juris_Civilis)

Because of this relationship with religion, the hammam became spatially associated with mosques over time. In this new context, the hammam gained a more religious designation. It was now used to perform the ghusul (full-body ablution) for hygienic and purification purposes.

A more practical difference with earlier hammams is the disappearance of water-baths in the cold-rooms. In the Islamic periods, cleansing with flowing water was preferred to soaking in baths.

18th Century etching of the Cold Room of a Hammam, by William H. Bartlett.

(From Julie Pardoe 1839: the beauties of the Bosphorus London: Library of Congress)

Different sources, from Arab geographers to legal doctrines, state that there are three essential elements for an (early) Islamic city: A mosque, a market and, public baths (Hammams). However while public hammams remained an important service for the people from the lower ranks of society, their popularity decreased because of a renewed popularity of private bathhouses for the rich and elite.

These new baths were built privately within the home and were often shared by family members and other close acquaintances.

From the 18th century onwards, traditional hammams became less and less embedded in Islamic societies and slowly began to disappear from the urban fabric.